Guarding relics easier than keeping staff

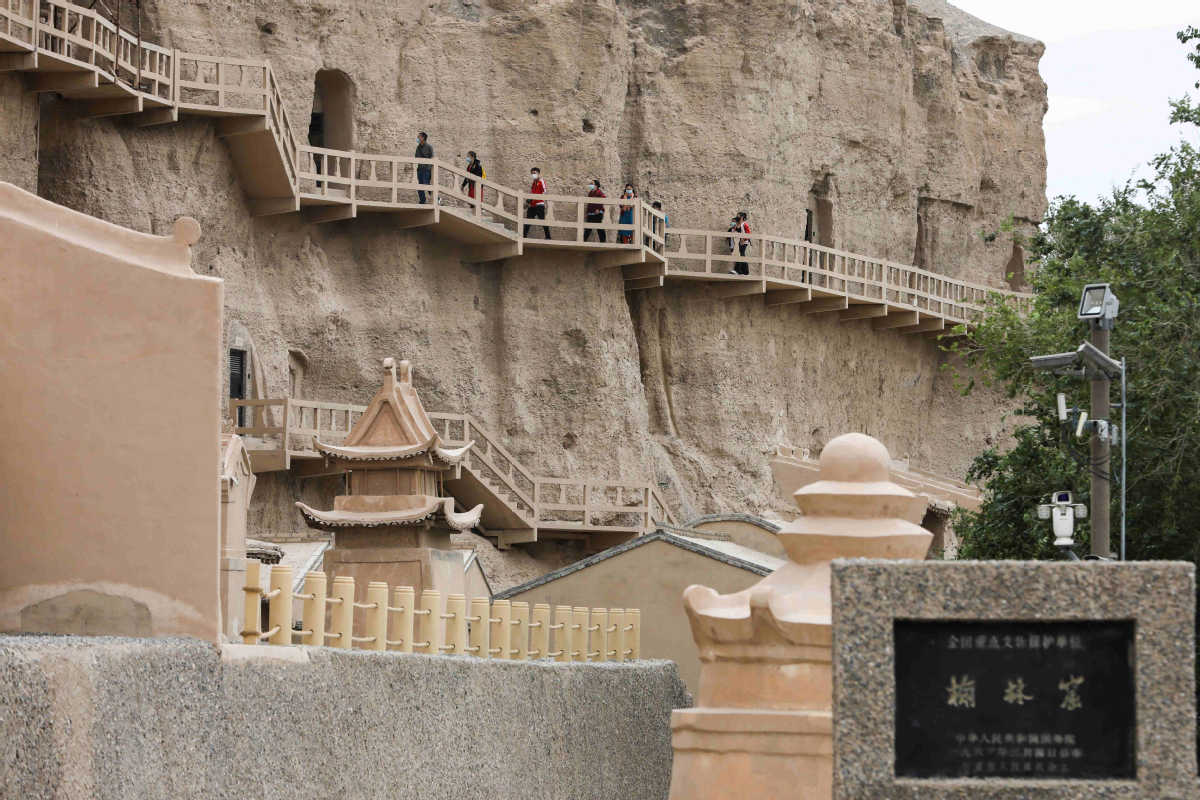

The Yulin Caves in Guazhou, Gansu province, have been under State protection since 1961. PHOTO/XINHUA

Despite more visitors and better research and infrastructure, some problems at Yulin Caves still hard to solve

In Northwest China's Gobi Desert today, there's little water and even fewer traces of humans, though the presence of many exquisite works of art suggests this was not always the case.

Just over a century ago in 1900, a Taoist monk discovered a cache of fine Buddhist art and scripts in the desert outside the ancient town of Dunhuang in Gansu province. Since then, the Mogao Grottoes, which are also known as the Thousand-Buddha Caves, and the location where the cache was discovered have become famous for their large-scale, well-preserved and precious treasures of Buddhist art.

While another Buddhist site-the Yulin Caves, some 168 kilometers to east of the Mogao Grottoes, in Guazhou county, Jiuquan city-remains less trodden, its murals and painted sculptures are of the same value as those of its more famous counterpart.

Song Zizhen, a cave guardian and director of the cultural relics conservation research institute of the Yulin Caves, has spent the last 14 years protecting and researching antiquities at the site and has seen Yulin rise from nothing.

"When I first arrived, employees barely made a living, let alone managed to attract tourists," he said.

Song said the nearest county is about 70 km away. Since they didn't own a car at the time, they had to grow vegetables and farm around the caves. "A dozen of us worked and lived here. In the spring, we planted trees, while in the autumn, we swept leaves," Song said. "When winter came, we swept the snow together."

Print

Print Mail

Mail